Distance, and not the ‘difference’, barricades the integration of cultures. Amidst the prejudices and stereotypes between Pakistani immigrants and host Italians, some ‘connectors’ are hopeful that increased interaction and frequent mixing can help create a multi-ethnic, co-existent and progressive society.

——–

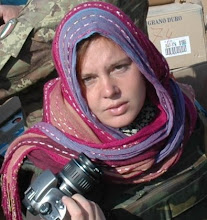

By Elisa Di Benedetto (Italy), Amer Farooq (Pakistan)

Terrorism, Burqa and War – Pakistan in Italy

“Terrorism, burqa and war”. This is Pakistan in the eyes of Italians Iqbal meets every day in Milan, where he lives with some friends, and immigrants like him, mostly from Pakistan. After arriving in Italy in 2002 following short stays in Germany, France and the Netherlands, Iqbal has chosen to remain, although his family lives in Pakistan. “I feel at home here. I love this country, especially the south in summers.”

Iqbal, 34, spends free time with friends from Pakistan; the contact with Italians is limited to sporadic occasions. “When I travel by train or by bus, women hold their bags tightly,” he says in a tone between resignation and amusement, recalling the questions that he is more frequently asked. “Sometimes people do not know much of Pakistan and confuse it with other countries. They even mistake it for Afghanistan.” So close on the map, especially in the popular imagination. “They ask me about war in Pakistan and I wonder what war they are talking about. They want to know about drugs production!”. Iqbal says he tries to talk about his country and explain the situation there, but sometimes feels “that even if people are saying “yes”, they don’t really understand what I’m trying to say”.

The story of Iqbal is not exclusive. Its a story of many – Ali, Ahmad, Naveed, Aslam and over 80 thousand immigrants of Pakistani origin in Italy. 70 percent of them live in Lombardia – North West of Italy – especially in Brescia, which has become “Brescia-stan” – reflective of an immigration that has been transforming over the years, becoming an integral part of the local community.

“While in the eighties Italy was a transit point for immigrants bound for Northern Europe, the restrictions introduced by England and Germany have encouraged the transformation of the immigration phenomenon that has a sedentary characteristic now,” says Ejaz Ahmad, Pakistani journalist and cultural mediator in Italy since 1989.

Emphasizing that immigration is something more than a temporary trend, Ejaz hints at the purchase of home ow nership.

nership.“Around 10 thousand Pakistanis have purchased homes, often through a loan,” continues Ejaz, who knows well this reality. “It is a signal of intention to stay.” Explaining further the significant features of Pakistanis’ immigration, Ejaz says “It’s usually the man who leaves his country, and his family joins him after a few years.” In Italy, immigrant Pakistanis are in industry as workers, and usually after 5-6 years they try to get self-employed by starting a business, especially in the food and telephony, fruits and vegetables shops, call centers and Internet points. “For them, the possibility of a business represents a quantum leap, a raise in the social position”.

Wine, Women, Money – Italy in Pakistan.

“When my son insisted on going to Italy, I thought I would never be able to see him again”, says Khan, 62, who lives some 100 kilometers south of capital city Islamabad, in the rural town of Chakwal, and runs a small grocery store.

Aslam, Khan’s 36-years old son, went to Italy 15 years ago by an agent who demanded a fortune for sending him to Italy on fictitious documents. Khan had to succumb to his son’s insistence who was ‘under a spell by the stories narrated to him by his cousin who had gone to Italy while Aslam was still a child’.

“My nephew told my son a lot about Italy and he was so fascinated by these stories that he even threatened me to give his life if I didn’t let him go’, says Khan who is now happy with his son. “I had double trouble in sending my son to Italy. It was really hard for me to meet the agent’s demand and secondly I was afraid that my son would ruin himself with wine and women’, adds Khan.

When asked how did he know that his son would be lost in wine and women in Italy, Khan said, “I asked people coming to my store if they had any idea about Italy and most of them told me that women in Italy use to lure Asian guys into love trap and alcohol uses to be their tool for this”.

To a query about the ‘Italian experience’ of those who warned him against sending his son to Italy, Khan guessed almost none of them had ever been to Italy.

Answering about the truthfulness of his fears, Khan said he doesn’t think they were well-founded, if it were like that my son would not have been able to support and visit us regularly. “I am financially more liberated now, my son sends a handsome amount every month and we have got a beautiful house with his money.”

Khan says his son was married to a cousin back home and he is happy with wife and two children. His son, who once migrated to Italy on fake documents is a legal resident now and plans to help his young nephews migrate to Italy through legal means. Aslam’s father is no more worried about the idea of his grandchildren planning to move to Italy, neither do their fathers.

Aslam’s brothers who run the family business, the grocery store, are more comfortable while planning about sending their children to Italy than their father when he was to send his son.

“My son would join his uncle and I am not worried that he would be indulged in ‘immoral’ activities”, says Akhtar, elder brother of Aslam. He, however, has different fears. A concern today is the news on the atmosphere created against immigrant Pakistanis.

“There is lot of news in media about difficult situation for Muslims in Europe and America and this worries me at times.”

However, he quickly adds, ‘that situation in Pakistan is equally bad as the security agencies are picking up people on slightest doubts, and even on their appearance if they have grown up beards that make them look like Taliban” . Akhtar hopes that situation would improve if the people are allowed to interact with the people of cultures different than theirs.

“The problem is not with the people, it is with the politicians’, says Akhtar who has only higher secondary level formal education but is an avid consumer of newspapers and news and talk shows on television.

Beyond prejudice

If in Pakistan, Pakistanis meet Italy and Italian culture through the media and the stories of people who migrated to Italy, even in Italy the media have a role in building public opinion and perceptions of immigrants, unfortunately feeding stereotypes and prejudices. But there are also examples of coexistence between two cultures so different, though often overlooked.

Behind the memory of Hina, who was killed in 2006 by her father, uncle and brother for being “too Western” in her lifestyle, there is a more hidden Pakistan, which comes through the spicy flavours of fast food, through craft shops and call centers. Here, the ‘borders’ become more tenuous and the Pakistani and Italian cultures meet.

The Connectors

Cross-cultural dialogue and mutual understanding are enhanced by the institutions, associations and individuals working to help Italians know Pakistan and Pakistanis understand and know the country that hosts them; something that can help them integrate without abandoning their identity.

Ejaz Ahmad is one of them. He arrived in Italy to escape the tyrant military regime under General Zia in eighties with a degree in mass communications from the University of Lahore and experience in practical journalism. Now Ejaz lives in Rome with his Italian wife and two sons. “I work every day to promote integration, understanding and the development of a multiethnic society,” he explains, describing his activities in schools to ensure that diversity may be perceived as a common heritage. “It is something in compliance with the Constitution of Italy”, says Ejaz who works to illustrate the phenomenon of new immigration and promote knowledge about the culture, traditions, history and politics of Pakistan.

Understanding the importance of cutural integration and eradication of stereotypes about the two cultures, Ejaz founded a monthly magazine in Urdu, Azad – meaning “Free”. Published in 5000 copies every month with the help of Western Union, Azad reaches Pakistani community in Italy, with reports from Pakistan, useful information for immigrants in Italy, information on immigration and the reality of Pakistan in Italy.

“It’s not easy to promote and spread our culture because Pakistani embassy here lacks a specific program for this and because immigrants live in communities with little contact with the Italian culture and society.” As confirmed by Ejaz, who is a member of the Islamic Council of the Italian Ministry of Interior, the relationship between Islam and the Italian institutions is very important. “It is not the difference, it is the ‘distance’ that causes problems.”

Though the story of Hina is still alive in public opinion, many are unaware that in 2009 the Italian national Under-15 cricket team won the European Championship, second division. An unexpected result, not only because the cricket is not among the most popular sports in Italy, but mainly because to give fame to Italy was a team that had only one player of Italian descent. Ten of the eleven players who took to the field were in fact young second-generation immigrants, children of immigrants from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. An example of how two cultures can come together and live together, the victory also had political implications, as in September current President of the Chamber of Deputies Gianfranco Fini, who has served as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs in Berlusconi’s government of 2001 to 2006, recalled the event to support the right of citizenship for those born in Italy, even with immigrant parents.

As said Akhtar, dialogue and integration are possible if there is a chance to meet and interact, if the differences are not perceived as a barrier, but an asset. Immigrants can be, though inconspicuous, ambassadors of their culture in Italy, and vice versa without abandoning their identity – and interestingly without “doing in Rome as the Romans do” .